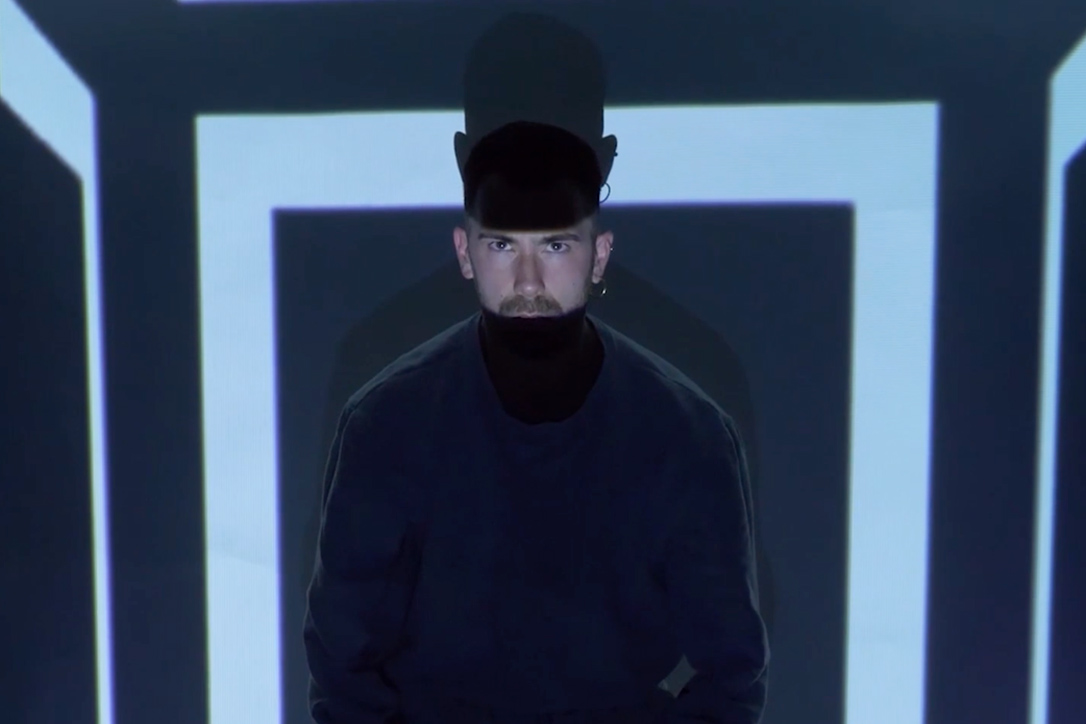

Dal 2013 è direttore artistico della compagnia ocram dance movement, compagnia associata a Scenario Pubblico centro di rilevante interesse Nazionale.

Ha firmato creazioni per la JCS di Stoccarda, il Conservatório Internacional de Ballet e Dança Annarella Sanchez, CZD2 giovane compagnia Zappalà danza, Balletto di Firenze ed è stato docente ospite presso la Copenhagen Contemporary Dance School.

Nel 2019 consegue la laurea in scienze politiche e relazioni internazionali, nello stesso anno è insignito del premio alla coreografia al Certamen Coreografico distrito de Tetuan.

Nel 2020 viene invitato come coreografo ospite presso l’Opera di Ljubljana. Dal 2022 è coreografo associato per il triennio 2022/25 del centro di rilevante interesse Nazionale Scenario Pubblico.

Since 2013 he has been the artistic director of ocram dance movement, dance company associated to Scenario Pubblic. He has been signing creations for John Cranko School of Stuttgart, Conservatório Internacional de Ballet and Dança Annarella Sanchez (Leiria, Portugal), CZD2, KAOS Balletto di Firenze and has been a guest teacher at Copenhagen Contemporary Dance School.

In 2019, he obtained a master’s degree in political science and international relations, in the same year, he was awarded with the choreographic award at the Certamen Coreografico distrito de Tetuan.

In 2020, he was invited as a guest choreographer at the Ljubljana Opera. Since 2022, he is an associate choreographer at Scenario Pubblico and, recently, he has been invited as a guest teacher at YGP Japan (Osaka).

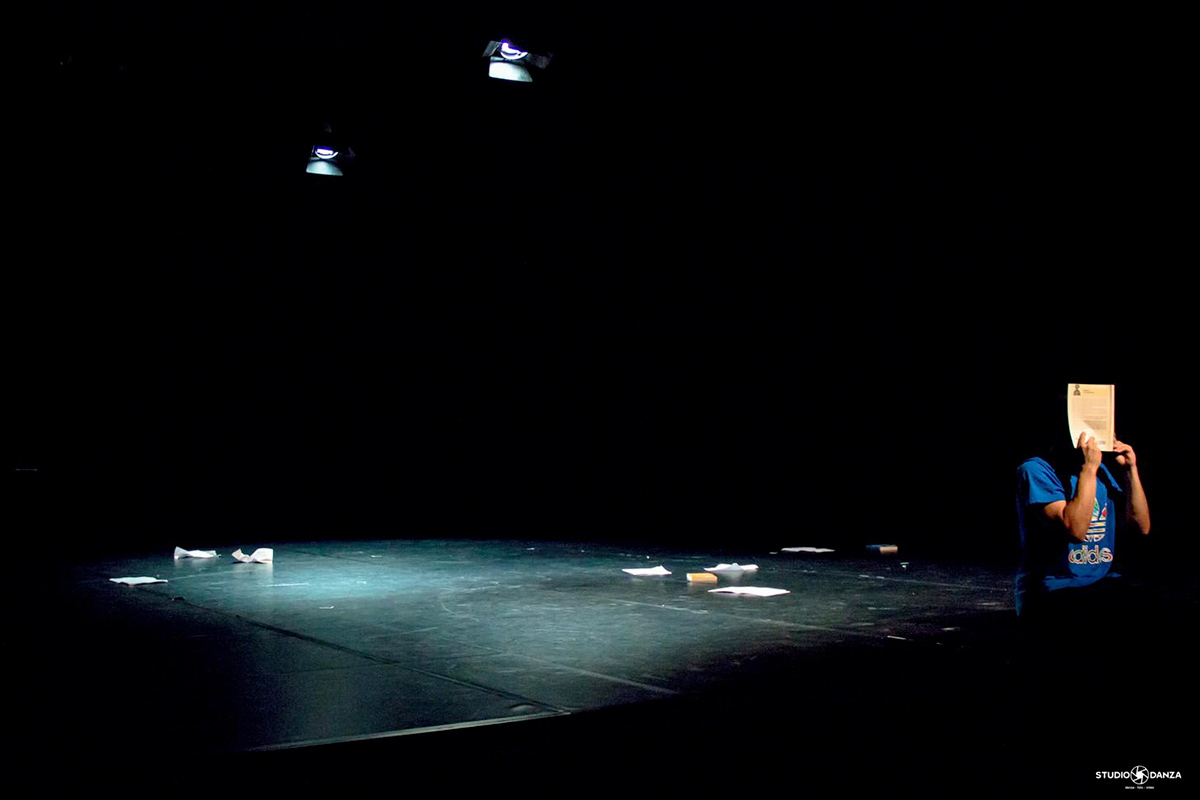

Artificio

luce, rumore, fumo

Come un gioco pirotecnico che incanta e lascia a bocca aperta, la vita dura il tempo di un’esplosione clamorosa, poi finisce. Ciò che rimane, al termine dello spettacolo esilarante, è la sensazione che sia durato troppo poco, lo stupore e una dolce amara malinconia, la voglia di ricominciare da capo, la paura che sia già troppo tardi.

Attraverso la metafora dei fuochi d’artificio, è possibile vivere le tre fasi più significative dell’esistenza umana e le sensazioni che predominano su ciascuna di esse.

L’infanzia, infatti, è caratterizzata dal sapore dell’attesa che precede l’evento, un piacere che ancora deve esistere, ma che è già più intenso del piacere stesso che verrà. La vita di un bambino segue la logica del noto monito “hic et nunc”, ma in un’ accezione ben più ingenua e, forse, più genuina. I bambini colgono l’attimo nella sua essenza, non si preoccupano delle conseguenze delle proprie azioni, né ragionano a lungo prima di compiere una scelta. Questa loro avventatezza, figlia dell’immaturità, è forse ciò a cui aspira Orazio, provando a vivere nel “qui e ora” nonostante l’età adulta.

Ma l’infanzia non è replicabile nemmeno dal miglior poeta e con essa diviene introvabile anche il piacere godurioso che risiede nella preparazione.

La scintilla che accende il fuoco genera un’esplosione irreversibile e, in un attimo, si è adulti.

Il piacere non risiede più nell’attesa dei fuochi, ma è il fuoco stesso.

Luminoso, assordante e prorompente, è il momento di massima espressione del gioco pirotecnico e della vita umana, il culmine dello spettacolo.

Durante la prima età adulta tutto ruota attorno all’amore – l’amore per se stessi, l’amore per un’altra persona, l’amore per un progetto, l’amore per un animale e così via – e l’amore è il piacere stesso. La ricerca dell’amore è eccitante, la sua perdita è estenuante, ma è nell’amore vissuto e consumato che dimora il godimento umano, il resto è un contorno che arricchisce o depaupera.

Tuttavia, l’amore moderato è una prerogativa delle persone sagge e la saggezza è un traguardo che interessa un’altra fase della vita, la terza.

Un giovane adulto ama molto, e molte volte, e il sentimento genera luce e rumore, ma “gioie violente hanno fini violente. Muoiono nel loro trionfo, come la polvere da sparo e il fuoco che si consumano al primo bacio”. Se Romeo e Giulietta avessero avuto sessantacinque anni o poco più, forse avrebbero amato in silenzio e con moderazione, ma sarebbero rimasti vivi almeno fino alla fine dei fuochi.

Si consuma lenta la vita durante la vecchiaia, anche il corpo rallenta la sua marcia verso un traguardo che, alla fine dei conti, spetta a tutti e che tutti vorrebbero evitare, tranne gli stoici.

L’ultimo sparo nel cielo segna la fine dei giochi e l’inizio di un buio nebuloso che vive di luce riflessa di una vita già vissuta.

light, noise, smoke

Like a pyrotechnic game that enchants and leaves you speechless, life lasts the time of a sensational explosion, then it ends. What remains, at the end of this exhilarating show, is the feeling that it was too short, the amazement, a bitter-sweet melancholy, the desire to start over, the fear that it is already too late.

Through the fireworks metaphor, it is possible to represent the three most significant phases of human existence and the feelings which predominate over each of them.

Childhood is actually characterized by the taste of waiting that precedes the event, a pleasure which has yet to exist, but which is already more intense than the pleasure itself that will come. The life of a child follows the logic of the well-known admonition “hic et nunc”, but in a far more naive and, perhaps, more genuine meaning. Children seize the moment in its essence, they don’t worry about the consequences of their actions, nor do they think for a long time before making a choice. This rashness of theirs, daughter of immaturity, is perhaps what Horace aspires to, trying to live in the “here and now” despite adulthood.

But childhood cannot be replicated even by the most brilliant poet and, with it, the enjoyable pleasure which lies within the preparation becomes impossible to get.

The spark that ignites the fire generates an irreversible explosion and, in an instant, we are adults.

The pleasure no longer lies in waiting for the fires, but is the fire itself.

Bright, deafening and bursting, it is the moment of maximum expression of the pyrotechnic game and of human life, the culmination of the show.

During early adulthood everything revolves around love – love for oneself, love for another person, love for a project, love for an animal and so on – and love is pleasure itself too.

The search for love is exciting, its loss is exhausting, but human enjoyment dwells in lived and consumed love, the rest is a side dish which can enrich or impoverish.

However, moderate love is a prerogative of wise people and wisdom is an achievement that affects another phase of life, the third.

A young adult loves in a passionate way, and many times, and the feeling generates light and noise, but “violent joys get violent endings. They die in their triumph, like gunpowder and fire that are consumed in the first kiss”. If Romeo and Juliet had been sixty-five or so, perhaps they would have loved each other in silence and in moderation, but they would have remained alive at least until the end of their fires.

Life is consumed slowly in old age, even the body slows down its march towards a goal which, in the end, belongs to everyone and that everyone would like avoiding, except the Stoics.

The last shot in the sky marks the end of the games and the beginning of a nebulous darkness which lives on the reflection of a light of a life which has already been lived.